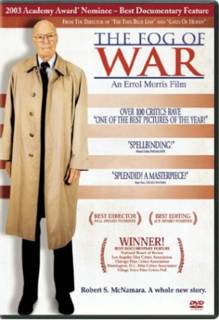

This documentary by Errol Morris is a running interview with controversial former Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara who served under Kennedy and Johnson. McNamara is unobtrusively filmed expressing his views on events in hindsight namely the Cuban missile crisis, WWII, and the Vietnam War. The interviews are interspaced with disturbing archival footage from these events. Fog of War is on one level an anecdotal recollection of McNamara's life: from his earliest memories of the elated celebrations at the end of WWI, fondly recalling his precocious youth in grade school topping his class, to his meteoric rise to the helm of Ford Motor Company for five weeks until his almost impromptu induction into the administration at the behest of JFK. 85-year-old McNamara is candid in front of the camera, his eyes reddening as he recalls painful experiences. The clarity of his memory belying his age and his intelligence and the collages of infamous historical episodes make for riveting viewing.

1. Empathize with your enemy.

2. Rationality will not save us.

3. There's something beyond one's self. 4. Maximize efficiency.

5. Proportionality should be a guideline in war.

"If we'd lost the war, we'd all have been prosecuted as war criminals." McNamara says: "And I think he's right. He, and I'd say I, were behaving as war criminals.... But what makes it immoral if you lose and not immoral if you win?" McNamara, still haunted by the sheer cruelty of the bombings, nevertheless grapples with the amoral nature of war as the victors are the ultimate arbiters of morality itself. 6. Get the data.

One senses the grudging respect for 7. Belief and seeing are both often wrong.

Often vilified as arrogant and termed Mac the "Knife" by the press during his much criticized stint as Secretary during the Vietnam War, McNamara makes an implict admission that the war was a wrong one. At Morris' prodding, he lets on that they [the Administration] saw what they wanted to believe in "They believed that we [ One questions why McNamara never learnt his first lesson, to empathise with the Vietnamese before invading the country. However, there are many more reasons for the gradual escalation into war beyond his control, one of which is the misplaced fear of the spread of Communism and Superpower rivalry. McNamara leaves the administration in acrimonious fashion in 1967, unable to agree with a war that he so strongly opposed morally, yet supported publicly. McNamara remains defensive about his role in the War, attributing ultimate responsibility for the conduct of war to the Commander-in-chief - the President, and adds almost with indignation that when he left in 1967, the casualty rate was 25,000 killed in action, less than half the eventual total of 58,000. 11. You can't change human nature.

Though he refused to draw analogies with the ongoing war in As the documentary draws to a close, McNamara startlingly says: "Never answer the question that is asked of you. Answer the question that you wished had been asked of you." This apparently undermines all he has said thus far, as it evokes images of McNamara, with his slicked back hair, facing the cameras during the Vietnam War, insisting beyond reason that according to General Westmoreland, good progress was being made in major operations. However, this is hardly the slurred monologue of a bitter man, but an engaging testimony that pares McNamara down as it provides insight to the machinations of a complex mind - dispassionate and methodical yet sensitive and emotional. The luminous intellect of McNamara stands out as we view historical events through the eyes of a battled-hardened Cold-warrior, skilfully captured (almost) unadorned. Labels: Movie Reviews

Genre: Documentary

Director: Errol Morris

Cast: Robert S. McNamara

Runtime: 107 min

Fog of War succinctly summarises the eleven lessons McNamara draws upon.

This is in relation to the Cuban missile crisis, in which McNamara does not revel in the triumphalism of having had a part in averting a world nuclear crisis, but proclaims that luck was on

McNamara questions the relevance of rationality when the possibility of total destruction via nuclear warheads is in the hands of one leader. He suggests that only luck prevented the Cuban missile crisis from escalating into nuclear war, this in spite of rational men at the helm of government.

In WWII, McNamara was stationed in

McNamara's and his teams research led to the adoption of a new method of bombing of 67 Japanese cities, called firebombing, in which the high altitude B29s were to descend from their usual 23,000 feet to 5,000 feet, dropping incendiary bombs. 100,000 civilians were killed in

The main reason for loss in bombing efficiency in WWII was the high rate of aborted missions which stood at 20%. McNamara's research concluded that most of the reasons for abortion were spurious and the aborted missions were the result of pilot cowardice.

8. Be prepared to reexamine your reasoning.

9. In order to do good, you may have to engage in evil.

10. Never say never.

He says:

Definitely not a Wilsonian pacifist, McNamara believes that wars would go on as human nature is predisposed towards conflict. But he offers his views on

"I do not believe that we should ever apply that economic, political, and military power unilaterally. If we had followed that rule in

Name: Gvoz

D.O.B: 7 Feb 1983

Horoscope: Aquarius

Home: Eastside SG

Favs:Alt.bands,Loungin,

Politics,History

Radio.Head

AtEase.Web

Foreign//Affairs

NY//Times

CfR

PaV.G

VaN.Era

Ta.Ryn

Tree.sia

Se.Rene

X.Wei

AvE

PaM

Ru.tH